Moroccan Knitting and the History of Knitting

The history of knitting has intrigued me since my early 20s when my mom gave me Nancy Bush’s book, Folk Socks: The History and Techniques of Handknitted Footwear, for my birthday. It was in the pages of Folk Socks that I first learned about knitting in northern Africa. Nancy’s medieval Egyptian sock pattern was one of the first written sock patterns I ever followed. It was a formative experience recreating an object that knitters generations before me had made. Knitting had always made me feel connected to the past and to other knitters, but making Nancy’s Mamluke Socks (pp. 76-78) made the world of medieval Egypt just that much more tangible.

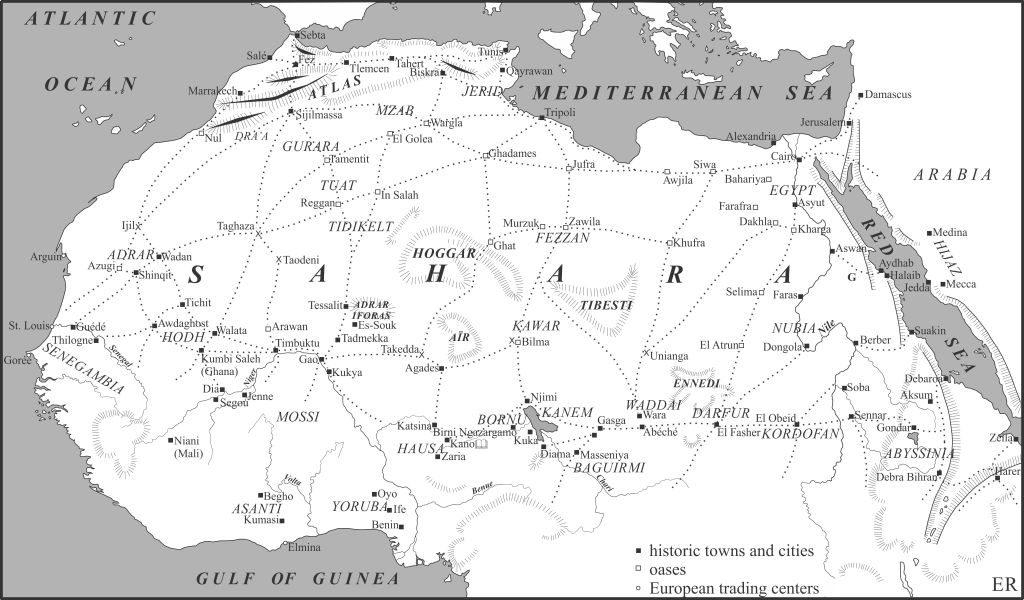

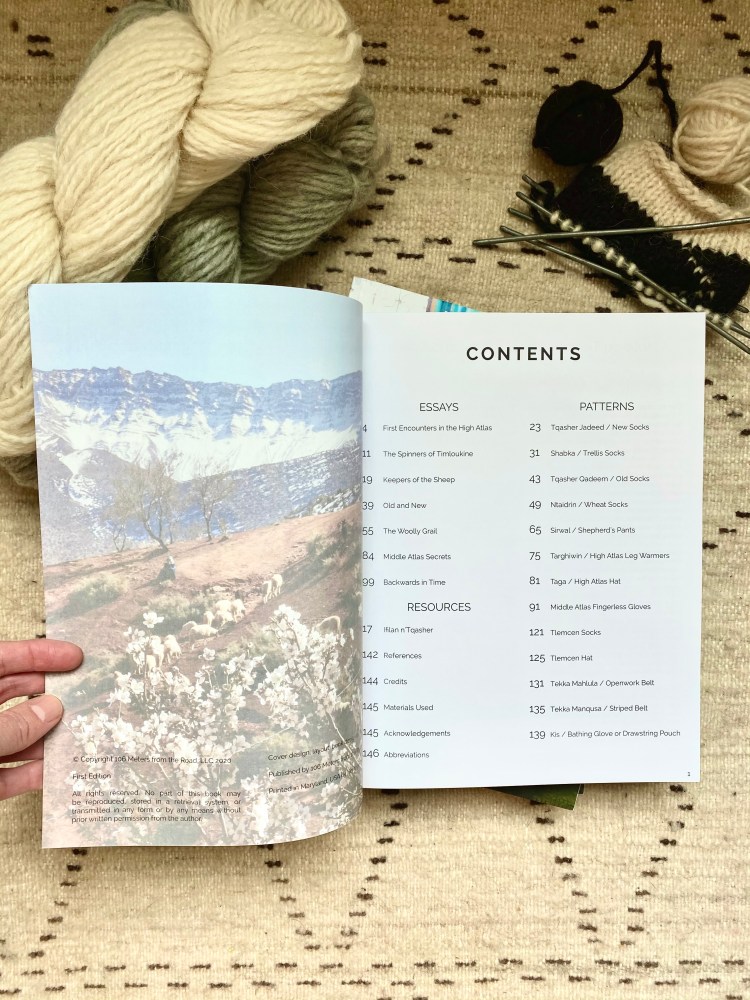

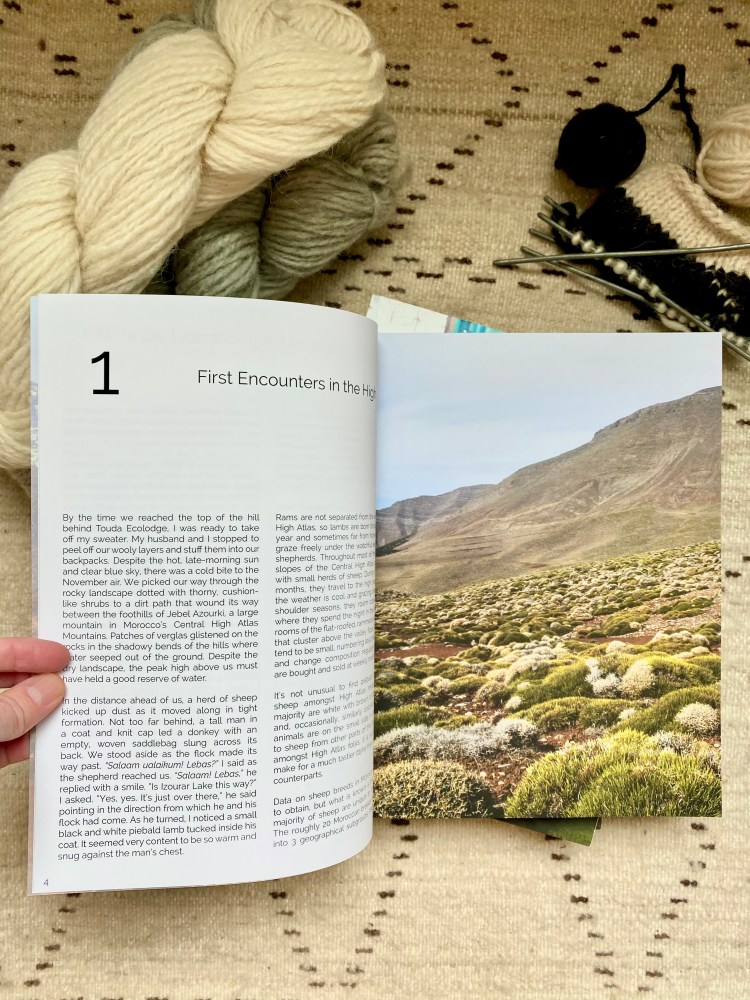

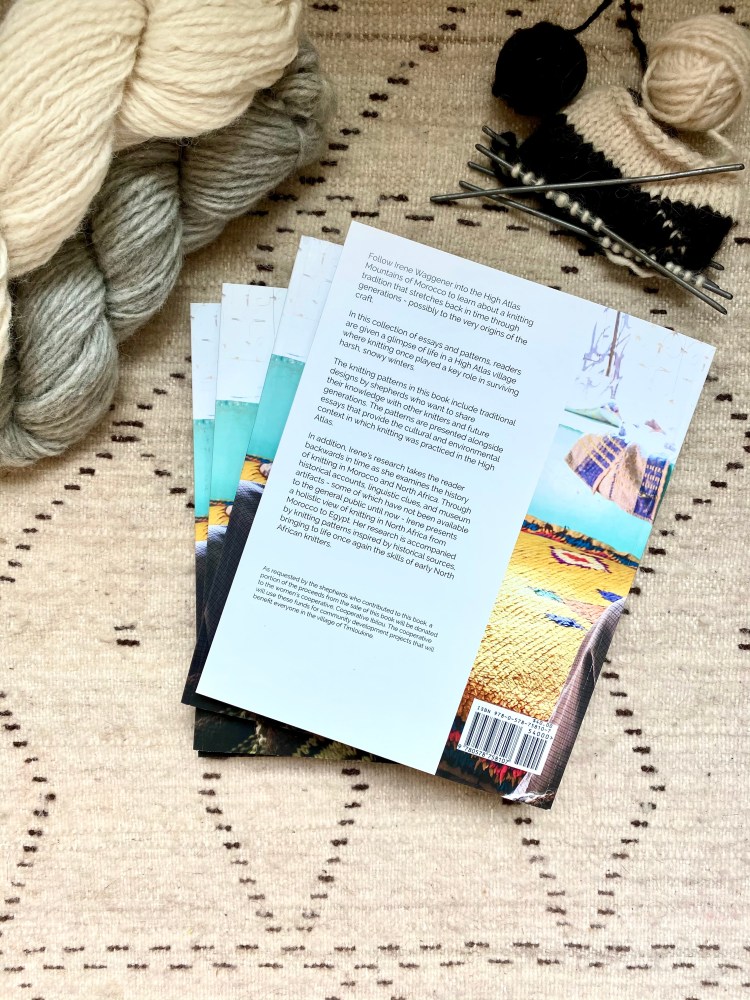

Over a decade later, I was living in Morocco when I learned of an indigenous knitting tradition in the Atlas mountains. Remembering what I had read in Nancy’s book, I couldn’t help but wonder if the Moroccan tradition might be related to the medieval Egyptian tradition. After all, medieval Spain also produced very complex and beautifully knitted objects. And, what lies between Spain and Egypt? Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya. It seems highly unlikely that knitting just skipped over most of the northern half of Africa to arrive in the Iberian peninsula (or vice versa). Living in Niger (2010-2012) had taught me about trade routes and the migration of people, ideas, and goods throughout the northern half of the African continent – not to mention the fact that people had been migrating between Iberia and the Maghreb (western North Africa) for centuries. It didn’t seem too far fetched to me that if knitting was happening in medieval Egypt and Spain, then it was probably also happening in medieval Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco. And so, I set out to connect Moroccan knitting to medieval Egyptian knitting by working backwards in time from the ethnographic collections and writings of French colonialists in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia to the material evidence from medieval Egypt. You can read about this work in my book, Keepers of the Sheep: Knitting in Morocco’s High Atlas and Beyond.

Why Moroccan Knitters Matter

The fact that there are people in Morocco who still know how to knit in the old way is special indeed. These knitters learned to knit from their elders, who learned from theirs, going back who knows how far. If their tradition is related to that of medieval Egypt and Spain, then they are a living link between the past and the present. I do not mean to imply that their knitting tradition was passed down unchanged over the centuries. Changes undoubtedly took place, since culture always evolves. But, it’s possible that some techniques and styles survived. What insight might these northern African knitters bring to the silent objects of northern Africa’s past? What can they and their knitting knowledge teach us about the history of their homelands and the connectivity between that homeland and other lands and peoples? Might these knitters and their knitting tradition contribute to piecing together a more nuanced understanding of interactions between the peoples of Africa, Europe, and beyond?

Why Heritage Knitting Techniques Matter

I believe that knitting techniques and styles can act as signatures of particular places and the people within those places. The way a person knits the toe or heel of a sock is kind of like the way a person shapes a ceramic pot or a stone tool. In archaeology, pots, tools, and the techniques for making them define cultural influences and are used to map possible migration, interaction, and exchange. Can knitting be used in the same way? Being able to map particular knitting techniques might help us ‘see’ ancient networks of interaction. However, in order to do this, we have to document what I call ‘old style,’ ‘heritage,’ or ‘indigenous’ knitting techniques (how to identify and what to call this kind of knitting is a whole other topic for debate). What I am referring to is the type of knitting people did before the dissemination of written knitting patterns, enforced colonial craft education, and YouTube.* Collaborating with those who still posses this type of knowledge and examining knitted artifacts from the past can help us better understand knitting styles and how they may (or may not) have influenced one another. The more information we have from these sources, the more reliable and clearer the picture will be.

Moroccan Knitters Today

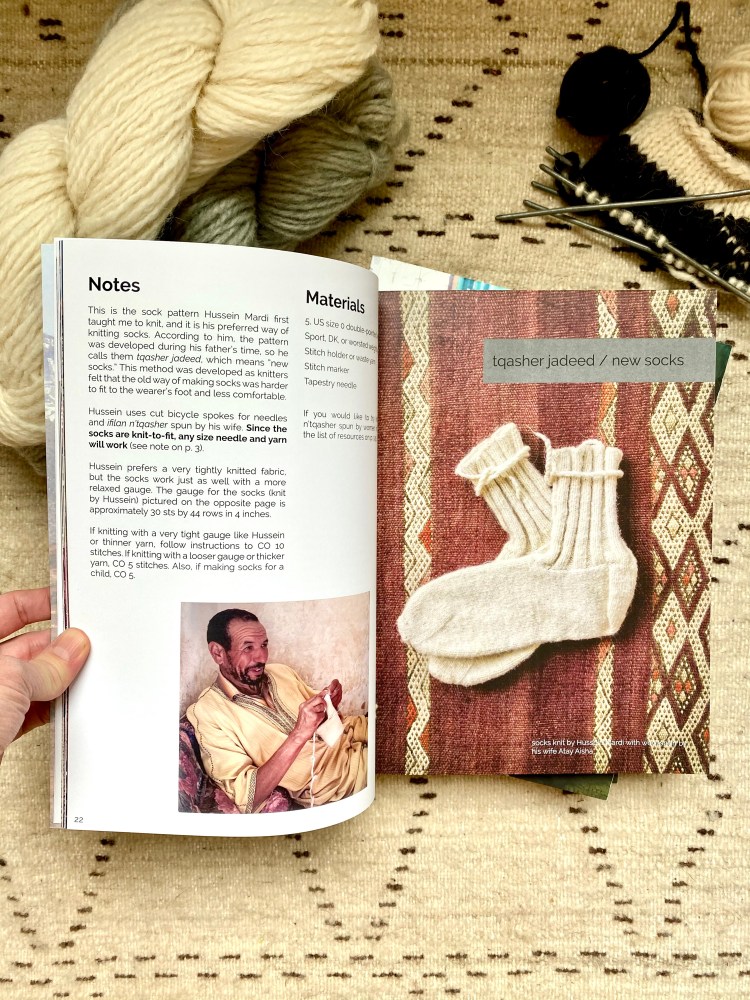

Unfortunately, the number of people who still posses these ‘old style’ skills is rapidly diminishing. Access to mass-produced products, changes in fashion, and changes in lifestyle affecting craft transmission are contributing to the rapid disappearance of indigenous knitting practices like that of Morocco. When I lived there, it took several trips from my home in Rabat to the High Atlas mountains to find people who still knit in the old way. In the end, thanks to help from artisans with the Anou, I was able to locate knitters in one particular valley of the High Atlas that had remained fairly isolated until relatively recently. All of the knitters I worked with in that valley were elderly, and they no longer produced the same range of products their forebears had made. They still knit socks, but pants, sweaters, leg warmers, hats, and mittens seemed to have fallen out of their repertoire. Some didn’t even knit anymore.

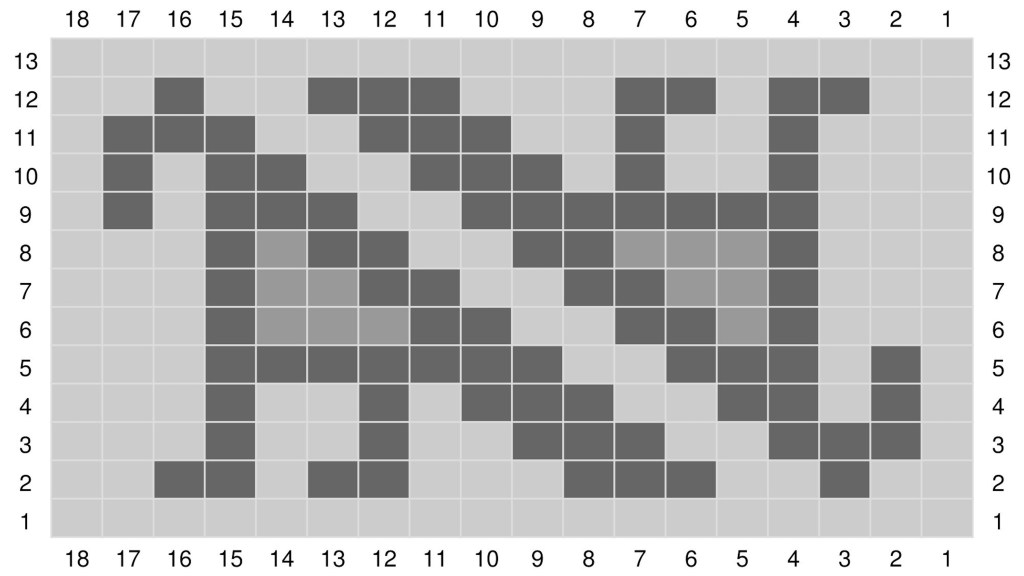

The situation in the Middle Atlas was more acute. After learning about the colorful, tessellating leg warmers Middle Atlas Amazigh men made for their brides, I tried on a number of occasions to locate ‘old style’ knitters but had no luck. In the end, I had to rely on objects at the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris and very limited anecdotes from colonial ethnographers and artists to develop a hypothesis for how the distinctive Middle Atlas leg warmers were knit. The motif used for women’s leg warmers is very important because a particular knitting technique is needed to achieve the design: intarsia-in-the-round. While intarsia is known and used in other parts of the world, the way in which it is executed in the Middle Atlas leg warmers is unique, as far as I know. This represents a major ‘signature’ that could help us better understand the development and dissemination of knitting across northern Africa.

Middle Atlas Knitting and Medieval Egyptian Knitted Fragments

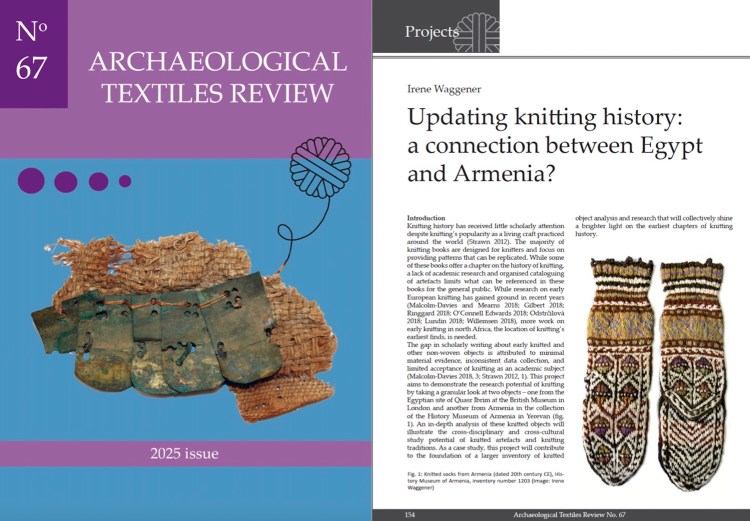

Intriguingly, a design element of Middle Atlas leg warmers echos a design element in medieval Egyptian knitted artifacts. In his seminal book, A History of Hand Knitting, Richard Rutt describes fragments that bear a “design peculiarity” in which the “unit of design is not the single stitch, roughly square (as in Fair Isle knitting), but… a unit of two stitches, one above the other in the same wale” (see p.37 for description and p. 38 for charted design). A similar design element can be seen in Middle Atlas leg warmers at the Musée du Quai Branly (see objects 71.1996.22.3.1-2 and 71.1937.34.3.1-2).

Another interesting parallel is the use of stranded and intarsia-in-the-round design elements in medieval Egyptian knitting. Richard Rutt believed that the use of intarsia in these pieces indicated that they had been knitted flat (p.37). However, the intarsia-in-the-round technique employed by Middle Atlas knitters encourages us to revisit this idea. In fact, intarsia-in-the-round is also used by knitters from western Asian knitting traditions, albeit in a different way (see Priscilla Gibson-Robert’s book, Ethnic Socks and Stockings: A Compendium of Eastern Design and Technique. For possible connections between western Asian and northern African knitting see my post here). In my opinion, both the doubled unit of design in the same wale and the use of intarsia in the round in medieval Egyptian and Middle Atlas knitting are interesting ‘signatures’ that warrant further investigation.

Finally, the Middle Atlas leg warmer motifs are strikingly similar to those on a fragment at the Whitworth Museum in Manchester (inventory number T.1968.438). According to Anne-Marie Decker, the piece was made by nalbinding using an intarsia technique. While she says the provenance is unknown, it is assumed to be from Coptic Egypt. This colorful fragment and the Middle Atlas leg warmers could shed light on the shift from nalbinding to knitting as well as interactions across northern Africa.

Spreading the Word About Middle Atlas Knitting

It would be best to hear and learn from Middle Atlas knitters themselves; however, there appear to be very few, if none at all, left. I believe that this unique and beautiful knitting tradition deserves to be recognized alongside other popular traditions like Fair Isle, Cowichan, and Nordic knitting. Since very little information is available about Moroccan knitting in general, I am making my notes for the Middle Atlas intarsia-in-the-round motif available here in the hopes of spreading the word about Moroccan knitting; encouraging its revival and study; and promoting Moroccan skills and knowledge in knitting history research. These notes first appeared in my Middle Atlas Skirt Pattern, which includes a step-by-step guide to intarsia-in-the-round (with photos). You can purchase it here. As a self-funded, independent researcher with no institutional connections, pattern sales help me cover the costs associated with my work. If you do purchase the pattern, thank you very much for investing in my research on the history and practice of knitting in northern Africa and western Asia. If you don’t want to purchase the pattern but would still like to support my writing, please consider sending me a tip via Ko-fi. Thank you!

Notes

*Written patterns, colonial craft education, and YouTube also have their role to play in the development and practice of knitting. They are very much a part of knitting’s story and illuminate the ways in which people interact and share/spread ideas. They too are worthy of study and are needed for a complete picture of the craft.

Melting snow dripped from the eaves of the rammed-earth homes. My friend and I carefully picked our way through the slick mud of the narrow path that wound between the multi-storied buildings, trying our best to avoid the bone-chilling drops. Eventually, the path widened to a small square flanked on all sides by dwellings with timber doors. A small gray donkey was parked in front of one home. The saddle blanket and panier draped across its back suggested that its owner would be back momentarily.

Melting snow dripped from the eaves of the rammed-earth homes. My friend and I carefully picked our way through the slick mud of the narrow path that wound between the multi-storied buildings, trying our best to avoid the bone-chilling drops. Eventually, the path widened to a small square flanked on all sides by dwellings with timber doors. A small gray donkey was parked in front of one home. The saddle blanket and panier draped across its back suggested that its owner would be back momentarily.

It’s unclear exactly how long people have been knitting in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco. The French artist, Jean Besancenot, produced gouache paintings of Moroccan dress between 1934 and 1939. Two of these depict a woman from the Middle Atlas wearing knitted leg warmers and a man from the High Atlas wearing the pants Moah was showing me how to knit. Besancenot noted that the pants were used by hunters who would spend long hours in the snow while hunting mouflon. He also remarks that the pants must have ancient origins, and that they are depicted on Etruscan vases. However, as far as I know, there currently is no archaeological evidence of these pants or knitting in Morocco. The most we have is the living tradition that exists today, the oral histories of the people from these areas, and any written accounts from historians of the past. What does seem certain is that people have been knitting in the Atlas Mountains for quite some time; and that until quite recently, knitting played an important role in local textile traditions for keeping people warm.

It’s unclear exactly how long people have been knitting in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco. The French artist, Jean Besancenot, produced gouache paintings of Moroccan dress between 1934 and 1939. Two of these depict a woman from the Middle Atlas wearing knitted leg warmers and a man from the High Atlas wearing the pants Moah was showing me how to knit. Besancenot noted that the pants were used by hunters who would spend long hours in the snow while hunting mouflon. He also remarks that the pants must have ancient origins, and that they are depicted on Etruscan vases. However, as far as I know, there currently is no archaeological evidence of these pants or knitting in Morocco. The most we have is the living tradition that exists today, the oral histories of the people from these areas, and any written accounts from historians of the past. What does seem certain is that people have been knitting in the Atlas Mountains for quite some time; and that until quite recently, knitting played an important role in local textile traditions for keeping people warm.